A study by Massachusetts General Hospital saw investigators analyse the varying ways non-invasive ventilation is administered in hospitals and their corresponding outcomes

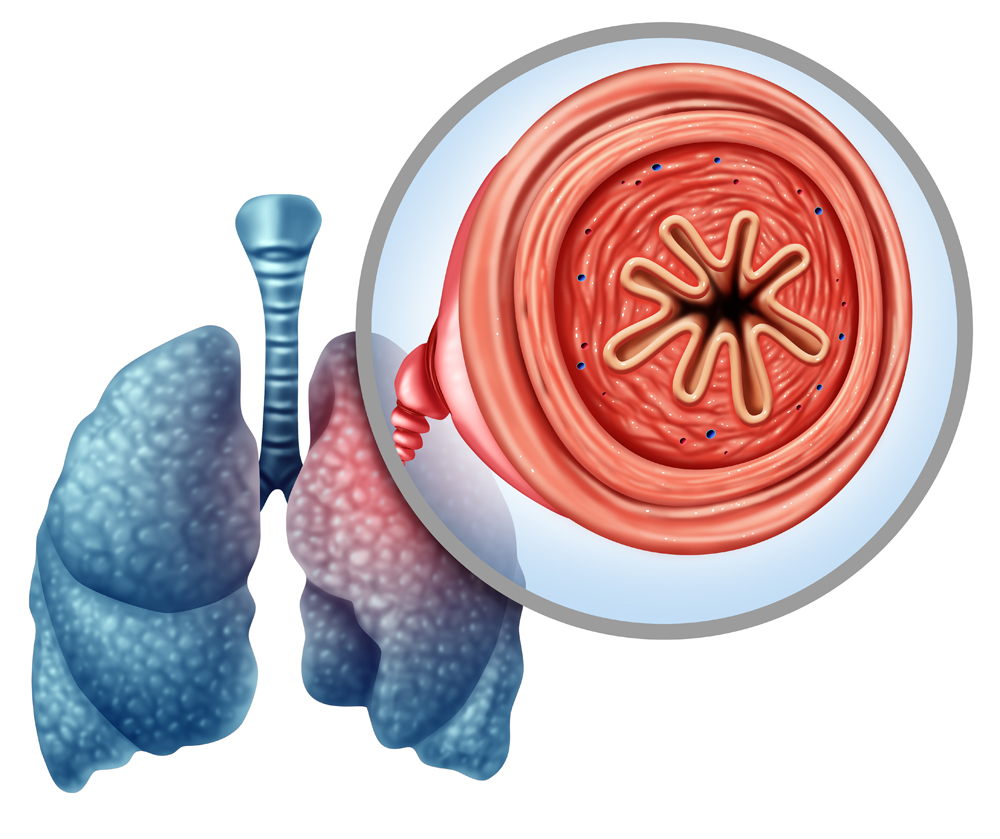

A study by Massachusetts General Hospital investigators has found broad variation in the way non-invasive ventilation is delivered in hospitals across the US (Credit: Shutterstock)

As coronavirus dominates healthcare and respiratory devices, a study by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators has found broad variation in the way non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is delivered in hospitals across the US. Laura C Myers of the MGH Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine and Chris Carlin, a respiratory consultant at Gartnavel General Hospital in Glasgow, talk to Sally Turner about the study’s findings and implications.

While coronavirus captures the headlines, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – which encompasses conditions that include emphysema and chronic bronchitis – remains a major cause of death and of emergency hospital admissions worldwide. The UK has one of the highest mortality rates for COPD in Europe, while rates are even higher in the US.

As COPD progresses, the airways become inflamed and narrowed, making it difficult to breathe. Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is an advanced respiratory therapy that delivers airway pressure via a mask, opening up the airways while also allowing the patient to exhale their carbon dioxide.

Laura C Myers is the co-author of a study by Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) investigators into the varying ways NIV is administered in hospitals and their corresponding outcomes. “It is really important for hospitals to use non-invasive ventilation for COPD patients, so much so that they are now being measured on this as part of national US guidelines,” she says. “When I studied at Harvard, during my clinical rotations I had noticed variations in how non-invasive ventilation was delivered to COPD patients. Even hospitals in the same city and within the same training programme delivered respiratory care differently.”

Differences in NIV care analysed

Myers noticed that some hospitals were bringing NIV critical care resources to the general medical unit to avoid transferring patients (and disrupting their care), while others were centralising critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). The study aimed to determine if this variation was more widespread and to measure whether patients being administered NIV in the ICU, versus on the general ward, have equivalent outcomes and cost.

For their research, the team used data from 424 hospitals from the State Inpatient Database maintained by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. They analysed data from 12 states that provided information on whether a patient was treated for COPD in an ICU. The data of more than 5,000 patients was analysed, revealing that 48% were treated on a general medical unit, while 52% were treated in an ICU.

Their findings, published in Critical Care Medicine, revealed no differences in length of stay or in-hospital deaths among patients with COPD receiving NIV treatment, regardless of whether they were treated on a general medical unit or an ICU.

“We interpreted this to mean that hospitals are probably administering care in a safe way, regardless of where in the hospital NIV is delivered,” says Myers. “We did standard risk adjustments, which acknowledges that data isn’t always perfect.”

Investigators noticed that patients in higher-ICU-using hospitals were more likely to receive invasive monitoring, such as central/arterial lines, which could indicate the need to monitor key respiratory parameters and deliver life-saving medications, or could indicate unnecessary procedures.

“However, there was little difference in rates of organ failure, which is a marker of severity of illness, between lower and higher-ICU-using hospitals,” notes Myers. “There was only a 0.15 difference in the average number of organ failures per patient between the lowest and highest-ICU-using hospitals, which is strikingly small.”

Admitting patients to the ICU is a costly enterprise for hospitals and the team’s research showed that when patients were treated on the general medical unit, costs per hospitalisation were around $1,500 less.

“From a policy standpoint, one could argue that if it’s unnecessary care to send someone to the ICU for NIV then treating them on the general ward could save patients’ and health insurers’ money,” says Myers. “The issue is, though, that hospitals have an incentive to keep their ICUs full because an ICU stay reimburses more than a stay on the ward.”

However, many hospitals operate their ICUs at full capacity, making an alternative delivery model of NIV an attractive prospect. “Although ICU capacity in the US is in the 60% range, the hospitals in Boston are always at 99% capacity in the ICU,” adds Myers. “So, acting on the findings of this study would probably create more availability in the ICUs in Boston, which would be positive. In general, though, it would decrease the amount of reimbursement hospitals receive from patient medical insurance if their ICUs aren’t actually full.”

Questions remain over standardisation

Could the study lay the foundation for a national policy that standardises the delivery of NIV in US hospitals? Safety protocols often advocate for standardisation as a means of improving outcomes, reducing waste and lowering costs, but Myers warns that standardisation is a complex issue.

“More work is needed before this approach could be implemented,” she concedes. “My hypothesis going into this study was that standardisation is the way to go, but now I think it is important to look at all the hospitals in the study and understand what their different models of care are.”

Myers is keen to ensure that there’s enough respiratory training and resources available in all major hospitals to manage a shift to standardising care on the general ward. Currently it is unclear what safety measures hospitals are using to be able to treat these patients safely on the ward. Some hospitals have dedicated respiratory floors with specially trained staff. Others may have a ‘safety huddle’ with protocols for transfer to the ICU.

“If we were to standardise everyone getting non-invasive respiration on the general ward, I would worry that hospitals that are used to delivering it in the ICU wouldn’t be able to bridge the gap from a safety standpoint,” she adds. “More training and resources may be needed.”

The study’s authors would like to undertake a further qualitative analysis to find out how hospitals are treating patients in these different scenarios, rather than relying solely on a quantitative analysis.

“This study does not reflect at all what we call ‘strain’ on the ward patients,” she continues. “If a patient on a general ward has greater needs as a result of having NIV that may require more nursing time and greater resources that is an important factor. It’s unclear what the impact on other patients on that ward might be, so we have to understand all of these ‘strain’ factors before any standardised practice around NIV should be implemented.”

Broader applications beyond the ward

The US and UK have very different healthcare models, so is the study of relevance in other healthcare contexts?

“It’s a great study,” says Chris Carlin, a respiratory consultant at Gartnavel General Hospital in Glasgow, “and a good example of getting insights from careful consideration and routine clinical data, with a clear message that can help improve value-based care.”

Carlin, who has conducted research into the efficacy of NIV, says similar studies in the UK and Australia have also reported positive outcomes using NIV in ward-based care. “There are different thresholds for admission to the ICU in the UK versus the US,” he continues. “In the UK, current practice with acute NIV is almost all ward rather than ICU-based.”

“Our colleagues in the UK are probably a step ahead of us in terms of using NIV in the home,” says Myers. “France and Denmark have also done some interesting studies on this.”

Home NIV has been provided for patients with neuromuscular diseases, chest wall diseases, spinal cord injury, obesity-related problems and other conditions for the past 30 years. A large randomised trial – HOT-HMV-UK – undertaken across the UK in 2017 reported significant benefits in the subset of patients with COPD and the highest risk respiratory failure phenotype (chronic/convalescent elevation of blood CO2 levels).

“Home NIV for COPD has been more widely applied in some European centres for a number of years,” says Carlin. “In the UK, we were awaiting the HOT-HMV trial results. A number of centres have been exploring ways to provide a realistic COPD-NIV service following on from this.”

Carlin’s work with his team in Glasgow has focused on “realistic delivery” using technology available within ventilators to assist in set-up. This approach avoids elective or prolonged hospital admissions, which are expensive for the National Health Service and not acceptable to patients.

“There’s lots of similar activity across the UK and Europe,” he adds. “For example, looking at alternative device therapies to support breathing (home nasal high-flow therapy). Also the data from the ventilators is potentially predictive of changes in patients’ conditions. Integrating this data and applying machine-learning evaluation might allow a reorientation of care to predictive-preventative rather than a reactive approach.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 25, 2020, of Practical Patient Care. The full issue can be viewed here.